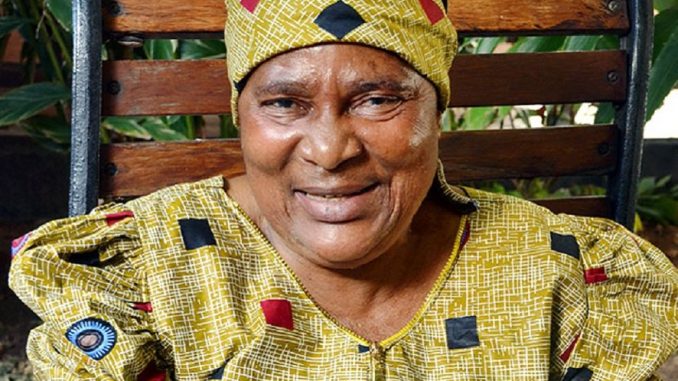

Pili Hussein was 31 when she ran away from her abusive husband in the late 1980s in search of work. Growing up in a large family in Tanzania, Hussein was one of 388 children of a livestock keeper who had many large farms and six wives.

_

_

_

_

For someone who does not like her upbringing, Hussein said: “My father treated me like a boy and I was given livestock to take care of – I didn’t like that life at all.”

She thought things would have been better in marriage but they turned out worse, forcing her to escape from a violent marriage.

Hussein arrived in a small Tanzanian town of Mererani, the only place in the world where mining for a rare, violet-blue gemstone called tanzanite takes place.

But since women were not allowed down the mines and she had no other option due to her lack of education, Hussein came up with a plan to enter the mine which is located south of Africa’s highest mountain, Kilimanjaro.

For almost a decade, she fooled her colleagues by disguising as a man to enable her to gain access down the mine.

“I took on the name of Mjomba Hussein (Uncle Hussein) … My ski cap hid my hair and part of my face. I abandoned my skirt for loose trousers and long-sleeved shirts.

“I worked alongside men for 10 – 12 hours every day; they never suspected that I was a woman. I drank Konyagi (local gin) and joked with the men about which village women I liked,” she told UN Women.

“The miners treated me as an equal and even sought my counsel. I was able to convince them to stop harassing the village women,” she said.

In an interview with the BBC, Hussein said nobody suspected her largely because she “acted like a gorilla.”

“I could fight, my language was bad, I could carry a big knife like a Maasai [warrior]. Nobody knew I was a woman because everything I was doing I was doing like a man.”

A year later, she made a big break, uncovering two massive clusters of tanzanite stones, 1000 grams and 800 grams each. With the money she made from her discovery, she built new homes for her father, mother and twin sister, purchased new tools for her work and even employed people to work for her.

Hussein would have gone on deceiving her colleagues in the mines if she had not been forced to reveal her true identity following a rape case.

A local woman had reported to the police that she had been raped by some of the miners and Hussein was picked up as a suspect.

At the police station, Hussein asked the officers to find a woman to physically examine her to prove her innocence. She was released soon after and for subsequent years, her fellow miners found it difficult to believe that she was a woman until 2001 when she married.

Regarded as a man by many, finding her husband came with its own issues, Hussein said, though she consequently succeeded.

“The question in his mind was always, ‘Is she really a woman?’” she recalled in the BBC interview. “It took five years for him to come closer to me.”

It’s been almost two decades since then, and Hussein is now blessed with her own mining company after applying for a mining license in the early 90s.

As of 2017, her mining company had employed about 70 workers, including only three women who worked as cooks and not miners.

“Some [women] wash the stones, some are brokers, some are cooking,” she said, “but they’re not going down in to the mines, it’s not easy to get women to do what I did,” said the 60-year-old Tanzanian miner who also has 150 acres of land, over a 100 cows and a tractor.

Out of her accomplishment, Hussein has been able to pay for the education of about 32 children from her family, including 30 nieces, nephews and grandchildren, yet she wouldn’t want her daughter to follow her path.

“I’m proud of what I did – it has made me rich, but it was hard for me,” she said.

“I want to make sure that my daughter goes to school, she gets an education and then she is able to run her life in a very different way, far away from what I experienced.”

Nevertheless, Hussein would love to see more women in the mining industry, though the sector has had more females than when she started.

“I want to work with younger women to teach them how to do business in the mining sector. I never had anyone to guide me and had to live with a false identity as a man, just to access the mines. It doesn’t have to be this way for the next generation,” she said.

Wow! This is an inspiration.We can achieve our dreams when determine to.