A ritual from the Ngondo festival — trip down memory lane

The Ngondo festival, which is a water-centred festival by the Sawa, that is, coastal peoples in Douala, Cameroon, was held annually until 1981 when it was banned by authorities due to some of its sacred rituals, especially the ceremony honouring the Jengu (the water spirit and deity worshipped by the Sawa).

In 1991, the festival was restored and has since not only exposed some of the sacred rituals that make the festival unique but has also exhibited the colourful culture of the Sawa people, including their beautiful arts and craft, their strength and how familiar they are with the sea.

The Ngondo festival, held in the first two weeks of December on the Wouri river banks in Douala, brings religion and tradition together as it involves communication between the “water gods” and the Sawa people.

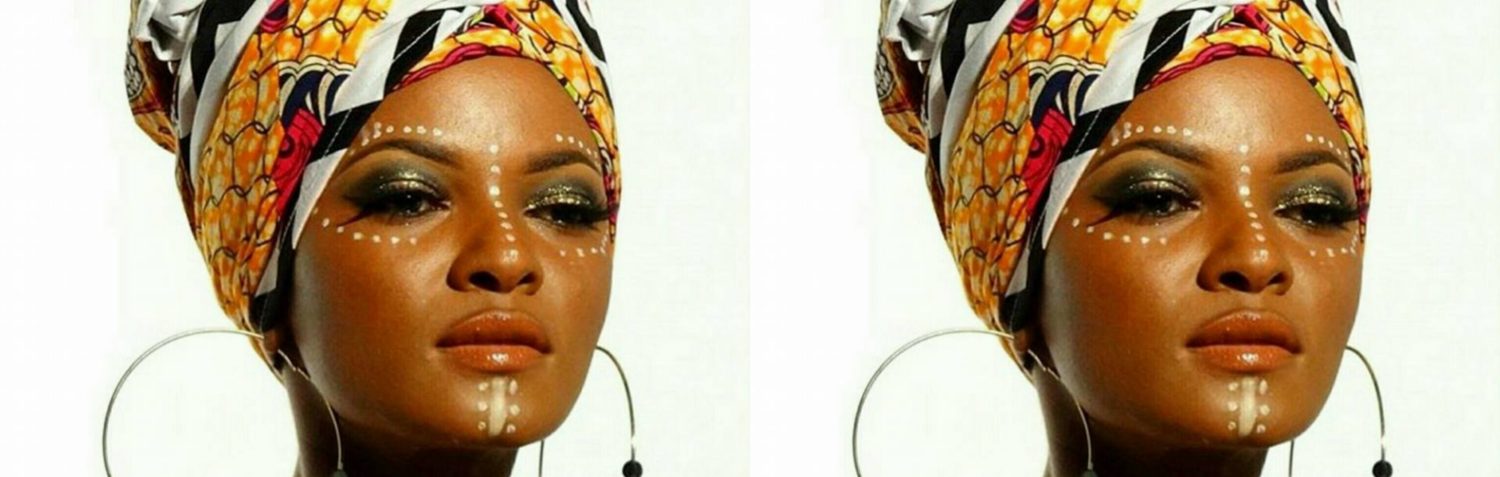

The festival comes with a lot of festivities including music and dance, a canoe race and a crowning of a Miss Ngondo, but the peak of the event is the ritual performed by the Jengu cult members, otherwise known as the immersion of the sacred vase.

According to locals, these cult members (or worshippers of Jengu) are sent by Sawa chiefs as messengers to the Jengu gods who are believed to be living in River Wouri and always bring good fortune to their worshippers.

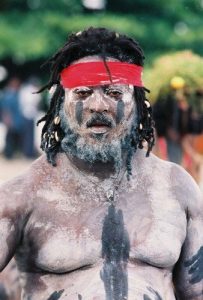

The said worshipper will dive and disappear into the river, stay there for almost an hour and will emerge with his body, his clothes and basket completely dry to the surprise of many.

“The immersion of the sacred vase starts with an assembly very early in the morning on the last day of the festival. Dignitaries in ceremonial dress come to the river accompanied by their staffs and followed by a dense crowd of people. Initiates on a pirogue look for a secret passage for the immersion of the sacred vase.

“An emissary goes into the Wouri with the vase to seek messages sent by the water divinities, the ‘Myengu’ (sirens). When the boatmen are immersing themselves into the water to the Jengu, the boatmen and the traditional priests, as well as other initiated elders, undertake a wild mass cries “yai assu yai” (Come assu come) meaning assu is an alternative name for Jengu. Once they have been brought to the surface, the people look unwet and the calabash they brought are interpreted by the ancients who meet in the sacred hut,” according to accounts by trip down memory lane.

Pirogue racing has traditionally been the most important sport among the Douala, with the sport reaching its peak during the German colonial period when organisers held races annually.

The Sawa people, as already mentioned, are the coastal people from the Douala, that is the Bantu-speaking people of the forest region of southern Cameroon living on the estuary of the Wouri River.

Tracing back their ancestry to a man named Mbedi, who would have one of his sons settle at the east bank of the Wouri river estuary, the Douala, by 1800, controlled Cameroon’s trade with the Europeans, and their concentrated settlement pattern developed due to this, according to sources.

They have been influential in Cameroon’s history due to this, coupled with their high rate of education, and wealth gained over centuries as slave traders and landowners.

For the larger part of the 19th century, there were two political–commercial kingdoms, Bell and Akwa but these were destroyed by the 1880s.

Douala served as the capital of the German Kamerun protectorate from 1884 to 1902 and also served as the capital of Cameroon in 1940–46.

“With its mixture of traditional, colonial, and modern architecture, Douala has grown rapidly since World War II and is the most populous city in the republic. Western-style residential areas alternate with neighbourhoods inhabited by unskilled migrants from rural Cameroon and other African countries,” according to Encyclopaedia Britannica.

It is today one of the major industrial centres of central Africa, and Cameroon’s largest city and major port, in charge of most of the country’s exports (mainly cocoa and coffee) as well as transit trade from Chad.

The Wouri estuary, through which the country derived its name, also supports a fishing and agricultural economy in which plantain and corn, oil palms, cassava, cocoyam are the principal crops.

The Wouri Bridge, 5,900 feet (1,800 metres) long, joins Douala to the port of Bonabéri and carries both road and rail traffic to western Cameroon.

The Douala trace descent patrilineally, and associations, or secret societies, were largely their instruments of social control. Their older religious system focused on a high god or a creator while others believed in the power of witchcraft and ancestors.

But by the 1970s, most Douala were nominal Christians and as compared to the past where diviners used the results of the canoe races to predict the future, today a Christian priest often presides instead.

The festival has also taken a more commercial turn with the presence of the sponsors whose Tee-shirts have replaced the traditional clothes.

BY MILDRED EUROPA TAYLOR

Source