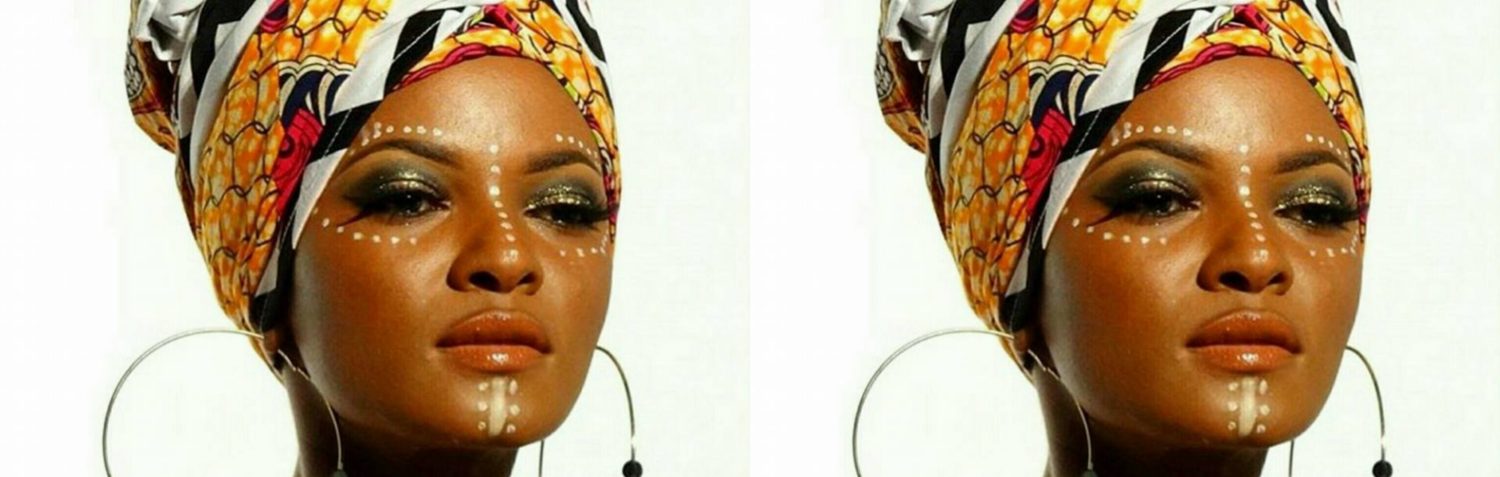

But while the Himba lifestyle catches the eye, it’s the elaborate hairstyles that really set them apart. Styles reference the status of the wearer. Himba women, by contrast, wear incredibly elaborate styles that change depending on whether or not they’re married and on how old they are.

‘Himba women use a lot of different things, including hair and straw, to create their dreadlocks.

A young Himba girl typically has two plaits of braided hair called ozondato, the form being determined by her oruzo (the paternal clan) she belongs. Girls who haven’t reached puberty always wear two plaits unless they are one of a set of twins in which case, they sport a single lock.

Young children tend to have shaved heads, although some have special haircuts that indicate they belong to a clan where taking care of goats with small ears is taboo – a tradition that extends to eating their meat.

A teenage girl with strands hanging over her face, means she has hit puberty and therefore has to hide her face from the men. When a woman has been married for a year or has had a child, she wears the erembe headdress, which is made from animal skin, on top of her head.

Keeping the elaborate dreadlocks in perfect shape is a challenge in itself, with women spending several hours a day tending to their hair and complexion.

‘Women take several hours each morning for beauty care and sleep on wooden pillows so they don’t ruin their hair in the night,’ explains Eric Lafforgue, the foremost anthropologist and photo-journalist. ‘The first task is to take care of their dreadlocks.

‘Then they cover themselves completely with a mixture made from ground ochre and fat, called otjize. ‘It acts as a sunscreen and insect repellent. If they do not have enough butter, they use vaseline.

He adds:The red colour that it gives to the skin is considered a sign of beauty and they smear the mixture all over themselves – not only on their skin and hair but also their clothes and jewellery.’

Lafforgue is also keen to debunk the myth that Himba people don’t wash. ‘This is wrong,’ he insists. ‘If they have access to water, they’ll take a bath, but as they live in arid places, it is a luxury.

‘Himbas who don’t have water use smoke to purify themselves and their clothes, which they “wash” by putting them into a basket with some incense made from the wood of the commiphora multijuga tree.’

Single men wear a plait called an ondatu on the back of their head.

Their elaborately braided hair, skin and clothes covered in a mixture of ground red rock and butter, the women of Namibia’s Himba ethnic group are a striking sight.

But while the women sport hairstyles of varying degrees of complexity, the men cover their heads with turbans from the moment they marry and never remove them; instead using an arrow-like implement to scratch the hair beneath the turban.

Who are the Himba people?

The Himba are beautiful, hardworking and peaceful agro-pastoralists people that forms a sub-set of the larger Herero ethnolinguistic group residing in Kaokoland, a vast stretch of land in northwestern Namibia and bordered by Angola to the north and the Skeleton Coast and Atlantic Ocean to the west. The friendly and extraordinary Himba people are closely related to the Herero people but they have resisted change and preserved their unique cultural heritage. About 240,000 Herero people live in Namibia, Botswana and Angola. They belong to the Bantu group of African nations.

Like other tribes living in the area, people depend on their cows to live and as a result, a Himba man without a herd of bovine companions isn’t considered worthy of respect.

The Himbas were impoverished by Nama cattle raiders in the middle of 1800’s and then forced to be hunter-gatherers. Because of these events they were called the Tjimba, derived form the word meaning aardvark, the animal that digs for its food. Many Himbas fled to Angola where they were called Ovahimba, meaning ‘beggars’. They left with their leader called Vita (”war”). After World War 1 he resettled his people in Kaokoland. Since these events the Himbas were living their nomadic pastoralist lives. But now more and more they have to reconcile traditional ways with European values.

‘Despite the above stated fact and though they live in little villages, the Himba are rich people. ‘The herds can be anything up to 200 cows, although they will never says how many cows they have – they keep it secret to avoid thieves.’

The Himba’s egalitarianism also extends to who gets to be in charge of what, with decisions split between men and women. ‘The Himba have a system of dual descent where every person is linked to two distinct groups of relatives: one through the line of the mother and the other through the father,’ explains Lafforgue. ‘Overall authority is in the hands of the men but economic issues are decided by the women.’

Clothing

Although some Himba wear clothes, among them the clans evangelised by the Germans in the 18th century who wear ornate Victorian ensembles called Hererotracht, for the majority, the focus is on hair and jewellery

Women wear a large white shell necklace called the ohumba, which is passed from mother to daughter. Equally popular, particularly among married women, are heavy necklaces made from copper or iron wire – much of which is taken from electric fencing.

‘Some wear keys and bullets as decoration as most of their houses don’t have locks,’ adds Lafforgue. ‘The necklaces of the older women can weigh several kilos but new ones are made with PVC tubes or from things given to them by tourists. That’s why you sometimes meet HImba women wearing bracelets that have an Arsenal logo!

‘Women also use omangetti seeds as decoration because they enjoy the noise they make when they walk. The adult Himba women all have beaded anklets called omohanga, where they hide their money. The anklets are also handy as a protection against venomous animal bites.’

Sadly, the Himba’s ancient way of life is becoming increasingly threatened with Western mores on dress and lifestyle becoming increasingly influential among younger people.

‘Everywhere tradition is giving way under the pressure of modern practices and new ideas,’ explains Lafforgue. ‘Himba women seem to want to keep to the old ways and they resist change more than men do.’

BY: Kweku Darko Ankrah